Introduction to Group Theory and Important Theorems

Definition of Group and Uses

- Different calculations have similar features

- Regular algebra

- Modular arithmetic

- Vectors

- Rotating a polygon

- Can algebra be made more “general” to allow results in one of these to be applied elsewhere?

- A group is defined by a set $S$, operation $\cdot$, and identity $e\in G$ (optional)

- Closure: $x\cdot y\in G\ \forall x,y\in G$

- Associativity: $x\cdot (y\cdot z)=(x\cdot y)\cdot z\ \forall x,y,z\in G$

- Conventionally $x\cdot y$ is “$x$ then $y$”, so $x\cdot y\cdot z$ means $x\cdot(y\cdot z)$

- Identity: $x\cdot e=e\cdot x\ \forall x\in G$

- Inverse: $\forall x\in G\ \exists x^{-1}\in G\ x\cdot x^{-1}=x^{-1}\cdot x=e$

Intuitive Understanding and Examples

- Symmetries of object

- Polygons without flipping is equivalent to modular arithmetic

- Dihedral groups: symmetries of polygons including flipping

- Notice the $\cdot$ operation in group doesn’t need to be commutative ($x\cdot y\neq y\cdot x$)

- Symmetries of polyhedrons

- $\mathbb{Z}$, $\mathbb{R}$, $\mathbb{C}$: translational symmetry

Visualization: cayley diagrams

Subgroups

- Subset that’s also a group

- Notation: subgroup $H\subset G$

- Example: $D_3$ group

Cosets (陪集)

- Define left coset $gH={gh:h\in H}$ $\forall g\in G$

- Right cosets: $Hg={hg:h\in H}$

- Size of cosets are equal to $\vert H\vert$

- $gh=gh’ \iff h = h’$, proven before

Lemma: cosets partition group into equal-sized pieces

- What algebraic manipulations can be done in group theory proofs?

- “Multiply” the same terms on both sides of the equation

- Need to multiply both on left or both on right

- Can’t divide by terms, but can “multiply” by inverse (if the element being taken inverse is in a group)

- E.g. $g_1g_3=g_2g_3\iff g_1g_3g_3^{-1}=g_2g_3g_3^{-1}\iff g_1e=g_2e\iff g_1=g_2$

- Can’t swap terms, but can start evaluating results from anywhere in a large “product”

- E.g. $g_1(g_2(g_2^{-1}g_3))=g_1((g_2g_2^{-1})g_3)=g_1(eg_3)=g_1g_3$

- Closure of group elements: $g_1g_2g_3^{-1}g_4g_2^{-1}…$ is still element of $G$

- No partial overlapping: $\forall g_1,g_2\in G$, either $g_1H=g_2H$ or $g_1H\cap g_2H=\varnothing$

- If $g_1H\cap g_2H\neq\varnothing$, then there exists $h_1$, $h_2$ so that $g_1h_1=g_2h_2$. Need to prove that for all $h\in H$ there exists $h’\in H$ so that $g_1h=g_2h’$

- $g_1h_1 = g_2h_2 \Rightarrow g_1h_1h_1^{-1}h = g_2h_2h_1^{-1}h \Rightarrow g_1h=g_2h_2h_1^{-1}h \Rightarrow$ the $h’$ we need to find is $h_2h_1^{-1}h$ which is in $H$ by closure and inverse properties

- Full coverage: $\forall g\in G\ \exists g’\ g\in g’H$: obvious, let $g’=g$

Lagrange’s Theorem: Order of Subgroup Divides Order of Group

- All possible distinct $gH$ of size $\vert H\vert $ “tiles” $G$

- $\vert H\vert $ divides $\vert G\vert $

Euclid’s algorithm and Bézout’s theorem

- Bézout’s theorem: $\forall\gcd(x,y)=1\ \exists a,b\neq 0\in\mathbb{Z}\ ax+by=1$

- Extension: $\forall\gcd(x,y)=1\ \exists a\neq 0\ ax\equiv 1\pmod y$

Fermat’s Little Theorem and Euler’s Totient Theorem

- The order of an element $g\in G$ is the smallest $n>0$ so that $g^n=e$. Since ${g^n\mid 0\leq n\leq \mathrm{order}(g)}$ forms a subgroup of $G$, the order of all elements in $G$ must also divide $\vert G\vert $

- Define group $G_n={a\in\mathbb{Z}\mid 0<a<n,\gcd(a,n)=1}$

- Operation is multiplication modulo $n$

- Identity is 1

- Closure is obvious

- Proved earlier that inverses exist

- Define $\phi(n)$ to be the size of $G_n$

- Euler’s totient theorem: $a^{\phi(n)}\equiv1\pmod n$ if $\gcd(a,n)=1$

- Special case: Fermat’s little theorem: $a^{p-1}\equiv 1\pmod p$ if $p$ is prime

Example: find $22^{98}$ modulo 105

- $\gcd(22, 105)=1$

- $\phi(105)=\phi(3\cdot5\cdot7)=105\cdot\frac{2}{3}\cdot\frac{4}{5}\cdot\frac{6}{7}=48$

- $22^{48}\equiv 1\pmod{105}$

- $22^{98}\equiv22^2\equiv64\pmod{105}$

Group Actions (群作用)

- Set $S$, $\forall g\in G,s\in S\ g\cdot s\in S$: group $G$ acts on $S$

Orbits (轨道) and Stabilizers (稳定子)

-

\[\mathrm{orb}(s)=\{g\cdot s\mid g\in G\}\]

- Path of $s$ when moved by all elements of group

- $\forall s_1,s_2\in S$, either $\mathrm{orb}(s_1)=\mathrm{orb}(s_2)$ or $\mathrm{orb}(s_1)\cap\mathrm{orb}(s_2)=\varnothing$

- Proof similar to cosets: no partial overlapping + full coverage, left as exercise

-

\[\mathrm{stab}(s)=\{g\in G\mid g\cdot s=s\}\]

- All $g$ that doesn’t change $s$

- Stabilizer forms a subgroup (proof left as exercise)

- The problem asks to find the number of distinct orbits in $G$

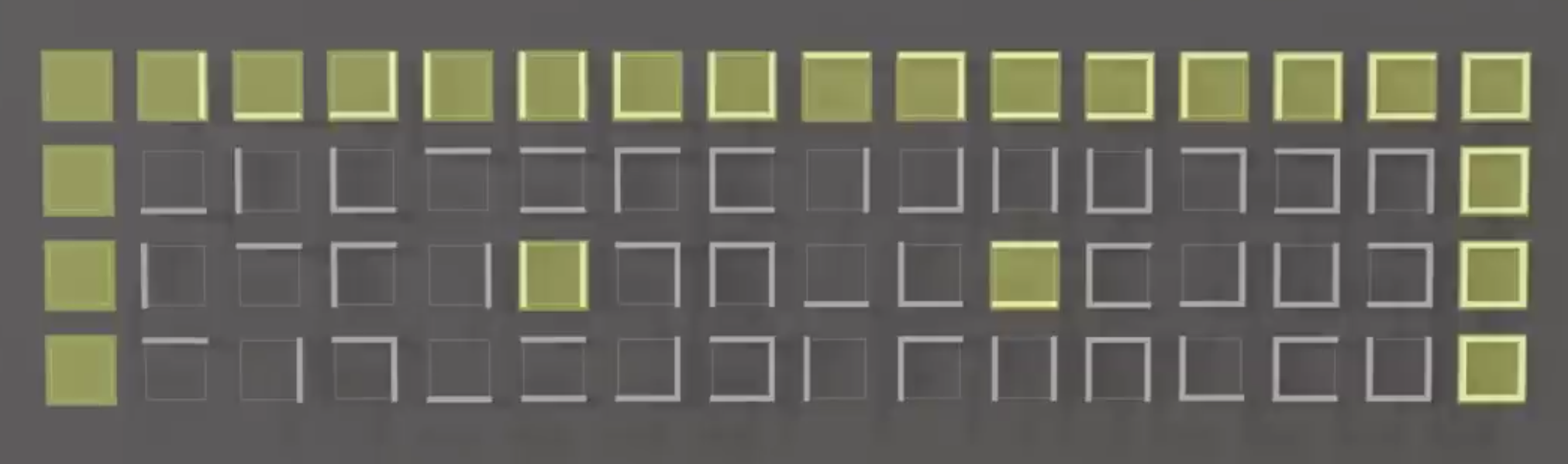

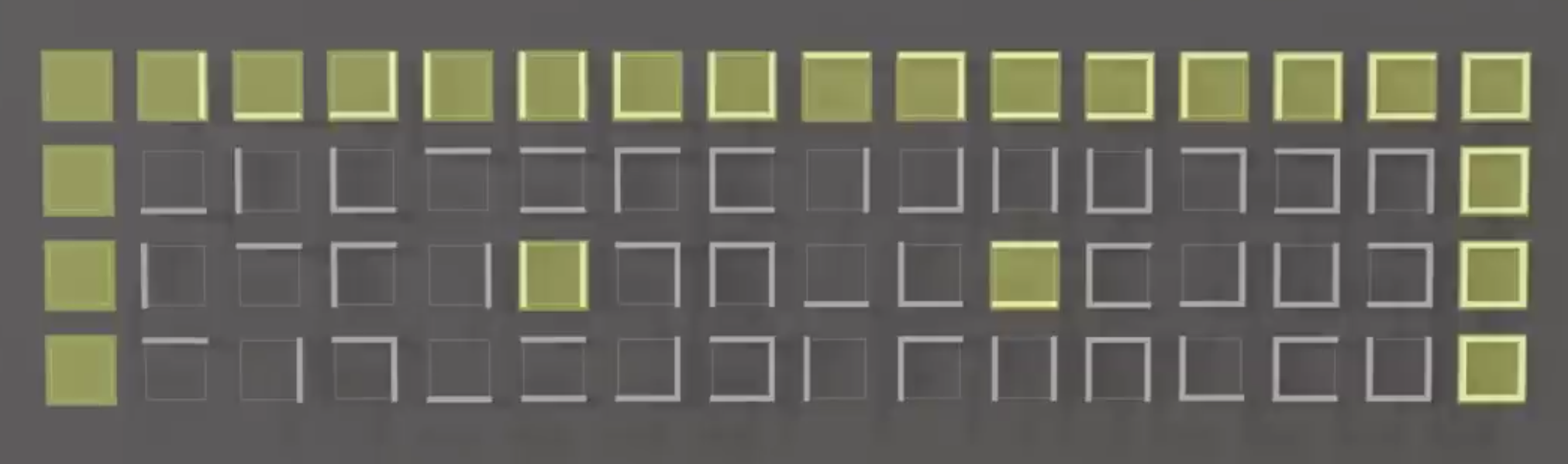

- Example:

- Each column is an $s\in S$, each row is a $g\in G$

- $G$ is group of all rotations of a square ($C_4$), $S$ is all subsets of a square’s edges

Orbit-stabilizer theorem

- $\forall s\in S\ \vert \mathrm{orb}(s)\vert \cdot\vert \mathrm{stab}(s)\vert =\vert G\vert $

- Define mapping $\phi(g\mathrm{stab}(s))=gs\ \forall s\in S$ (mapping cosets of $\mathrm{stab}(s)$ to elements in $\mathrm{orb}(s)$

- Exercise: proof that this mapping is 1-to-1

- $\vert \mathrm{orb}(s)\vert = \text{number of distinct }gs = \text{number of distinct }g\mathrm{stab}(s) = \frac{\vert G\vert }{\vert \mathrm{stab}(s)\vert }$

Burnside’s Lemma

- Define \(\mathrm{fix}(g)=\{s\in S\mid gs=s\}\)

- Important proof technique (in and outside group theory): double counting

- How to count the size of \(A=\{(g\in G, s\in S)\mid gs=s\}\)?

\[\begin{gather}

|A|=\sum_{g\in G}|\mathrm{fix}(g)| = \sum_{s\in S}|\mathrm{stab}(s)|\\

=\sum_{s\in S}\frac{|G|}{|\mathrm{orb}(s)|}\\

= \sum_{O\text{ orbit}}\sum_{s\in O}\frac{|G|}{|O|}\\

=\sum_{O\text{ orbit}}|G|\\

= \text{number of orbits}\cdot |G|

\end{gather}\]

- $\text{number of orbits}=\frac{1}{\vert G\vert }\cdot\sum_{g\in G}\vert \mathrm{fix}(g)\vert $

Problem: how many rotationally distinct subsets of the edges of the regular octagon are there?

- Identity: 1 element

- All subsets of edges are fixed points of this element, giving a total of $2^{12} = 4096$ fixed points

- Rotation along the center of a face: 4 axes ($\frac{8\text{ faces}}{2}$), 2 rotations for each axis, 8 elements

- 4 sets of edges, 3 each, must be either all chosen or all not chosen, a total of $2^{4} = 16$ fixed points

- Rotation along the midpoint of an edge: 6 axes, 1 rotation for each axis, 6 elements

- The 2 edges on the axis of rotation can be chosen or not chosen independently, the other 10 edges are in 5 pairs, each pair must be chosen or not chosen together, giving a total of $2^{7} = 128$ fixed points

- Rotation along a vertex: 3 axes, 3 rotations for each axis, 9 elements

- 3 sets of edges, 4 each, must be all chosen or all not chosen, giving a total of $2^{3} = 8$ fixed points

- And by Burnside’s lemma, the total number of orbits is

\(\vert \text{orb}_{G}\vert = \frac{1}{\vert G\vert } \cdot \sum_{g \in G}\vert \text{fix}(g)\vert = \frac{1}{24} \cdot (4096 + 8 \cdot 16 + 6 \cdot 128 + 9 \cdot 8) = (211)\)