Probability and Discrete Random Variables

1. Applying Set Theory to Probability

- Probability is a numerical value assigned to a set, indicating the likelihood of an event. A higher value corresponds to a greater probability. In this way, probability can be seen as a measurement similar to weight or temperature measurements.

- Fortunately for engineers, the language of probability (including the term probability itself) naturally relates to our everyday experiences. The fundamental concept is a repeatable experiment that consists of a procedure and observations. There is inherent uncertainty in the outcome. Here are some examples:

- Flip a coin. Does it land heads up or tails up?

- Walk to a bus stop. How long do you wait for the bus to arrive?

- Roll a die. Which number appears on the top face?

- Measure the temperature at noon each day. What is the temperature?

- As mentioned earlier, an experiment involves both a procedure and observations.

- We will describe models of experiments using a set of possible experimental outcomes. In the context of probability, we assign a precise meaning to the term “outcome.”

- Definition 0.1 (Outcome). An outcome of an experiment is any possible observation of that experiment.

- Definition 0.2 (Sample Space). The sample space of an experiment is the finest-grain, mutually exclusive, collectively exhaustive set of all possible outcomes.

- The finest-grain property ensures that all distinguishable outcomes are listed separately.

- Mutual exclusivity means that if one outcome occurs, no other can occur at the same time.

- Collective exhaustiveness requires that every possible outcome is included in the sample space.

- Example 0.3. Flip a coin and let it land on a table (this is the procedure) and then observe which side (head or tail) faces you after the coin lands (this is the observation).

- The sample space is $S= {h,t}$, where $h$ is the outcome “observe head,” and $t$ is the outcome “observe tail.”

- In everyday language, an event is something that happens. In the context of an experiment, an event occurs when a specific outcome is observed.

- Mathematically, an event is defined by the set of outcomes in the sample space where the phenomenon occurs. For each outcome, either the event happens or it does not.

- Definition 0.4 (Event). An event is a set of outcomes of an experiment.

| Set Algebra | Probability |

|---|---|

| Set | Event |

| Universal Set | Sample Space |

| Element | Outcomes |

2. Probability Axioms

-

Our model of an experiment includes a procedure and observations, which can be represented using set theory. This involves a sample space S (the universal set), outcomes s (elements of S), and events A (sets of elements). To complete the model, we assign a probability $P [A]$ to each event A in the sample space. Probability, in this context, is the relative frequency of an event occurring in a large number of experimental trials. Mathematically, this is defined by the following axioms.

- Definition 0.1 (Axioms of Probability). A probability measure $P [·]$ is a function that maps events in the sample space to real numbers such that:

- Axiom 1: For any event $A$, $P[A]\geq0$.

- Axiom 2: $P [S] = 1$.

- Axiom 3: For any countable collection $A_1, A_2, . . .$ of mutually exclusive events,

- Theorem 0.2. If $A=A_1\cup A_2 \cup … \cup A_m$ and $A_i \cap A_j=\varnothing$ for $i \not= j$, then

3. Consequence of the Axioms

- Theorem 0.1. The probability measure $P [·]$ satisfies:

- $P[A^c]=1-P[A]$

- For any A and B (not necessarily disjoint)

- If $A \subset B$, then $P [A] \leq P [B].$

- Theorem 0.2. For any event $A$ and event space ${B_1, B_2, …, B_m}$,

4. Conditional Probability

- Conditional probability $P [A\mid B]$ describes the likelihood of event A given that event B has occurred. This notation, read as “the probability of A given B,” provides insight into how probabilities can be used when only partial information is available.

- Definition 0.2 (Conditional probability). The conditional probability of the event A given the occurrence of the event B is

- Conditional probability is defined only when $P [B] > 0$.

- If $P [B] = 0$, it means $B$ never occurs, making it illogical to discuss $P [A\mid B]$.

-

Note that $P [A\mid B]$ is a valid probability measure relative to the sample space consisting of outcomes in $B$, and it satisfies the properties of the three axioms of probability.

- Example 0.4. Suppose you have a shuffled deck of cards, and you observe the top card. What is the conditional probability that the top card is the queen of hearts given that the top card is a red card?

- Sol:

- B ⇒ red card is on the top ⇒ $P[B] = \frac{26}{52} = \frac{1}{2}$

- A ⇒ Queen of hearts is on the top ⇒ $P[A]=\frac{1}{52}$

- $P[A\mid B]=\frac{P[AB]}{P[B]}=\frac{P[A]}{P[B]}=\frac{\frac{1}{52}}{\frac{1}{2}}=\frac{1}{26}$

5. Independence

- Definition 0.1 (Two Independent Events). Events $A$ and $B$ are independent if and only if

Independence and Disjoint Events

Independence Interpretation

- $P[A\mid B]=P[A]$

- If $A$ and $B$ are independent ⇒ $A$ and $B^c$ are independent

Disjoint Interpretation

- $P[A \cap B]=\emptyset$

Discrete Random Variables (DRV)

Random Variables and Their Relationships

- A probability model begins with an experiment, and each random variable is directly related to the experiment. There are three types of relationships:

- The random variable is the observation.

- The random variable is a function of the observation.

- The random variable is a function of another random variable.

- The value of a random variable is always derived from the outcome of the experiment, reflecting the relationship between the experiment and the random variable.

- Definition 0.1 (Random Variable). A random variable consists of an experiment with a probability measure $P [·]$ defined on a sample space $S$ and a function that assigns a real number to each outcome in the sample space of the experiment.

Identifying Random Variables

- A random variable $X$ can be represented by the function $X(s)$, which maps the sample outcome $s$ to the corresponding value of the random variable. The notation ${X= x}$ refers to the set of sample points $s\in S$ for which $X(s) = x$:

- Some examples of random variables include:

- A, the number of cars passing through a checkpoint in the next 10 minutes;

- C, The number of correct answers given on a quiz with 12 questions;

- M , the number of minutes until the next phone call is answered.

- Definition 0.4 (Discrete Random Variable). $X$ is a discrete random variable if the range of $X$ is a countable set

- Definition 0.5 (Finite Random Variable). $X$ is a finite random variable if the range is a finite set

Probability Mass Function

- In a discrete probability model, each outcome in the sample space is assigned a probability between 0 and 1. For a discrete random variable $X$, this model is expressed using a probability mass function (PMF), denoted as $P_X (x)$. The PMF provides the probability that $X$ takes on a specific value $x$. Although the argument of the PMF can be any real number, the PMF itself only assigns probabilities to the values that $X$ can assume.

- Definition 0.1 (Probability Mass Function (PMF)). The probability mass function (PMF) of the discrete random variable X is

- Notation:

- $X$ is the random variable.

- $x$ is a possible value of $X$.

- $P_X (x)$ is the PMF of $X$, assigning probabilities to values $x$.

- Theorem 0.2. For a discrete random variable $X$ with probability mass function $P_X (x)$ and range $S_X$ ,the following properties hold:

- For any $x$, $P_X (x) \geq 0$

- $\sum_{x \in S_X}P_X(x)=1$

- For any event $B \subseteq S_X$ , the probability that $X$ is in the set $B$ is

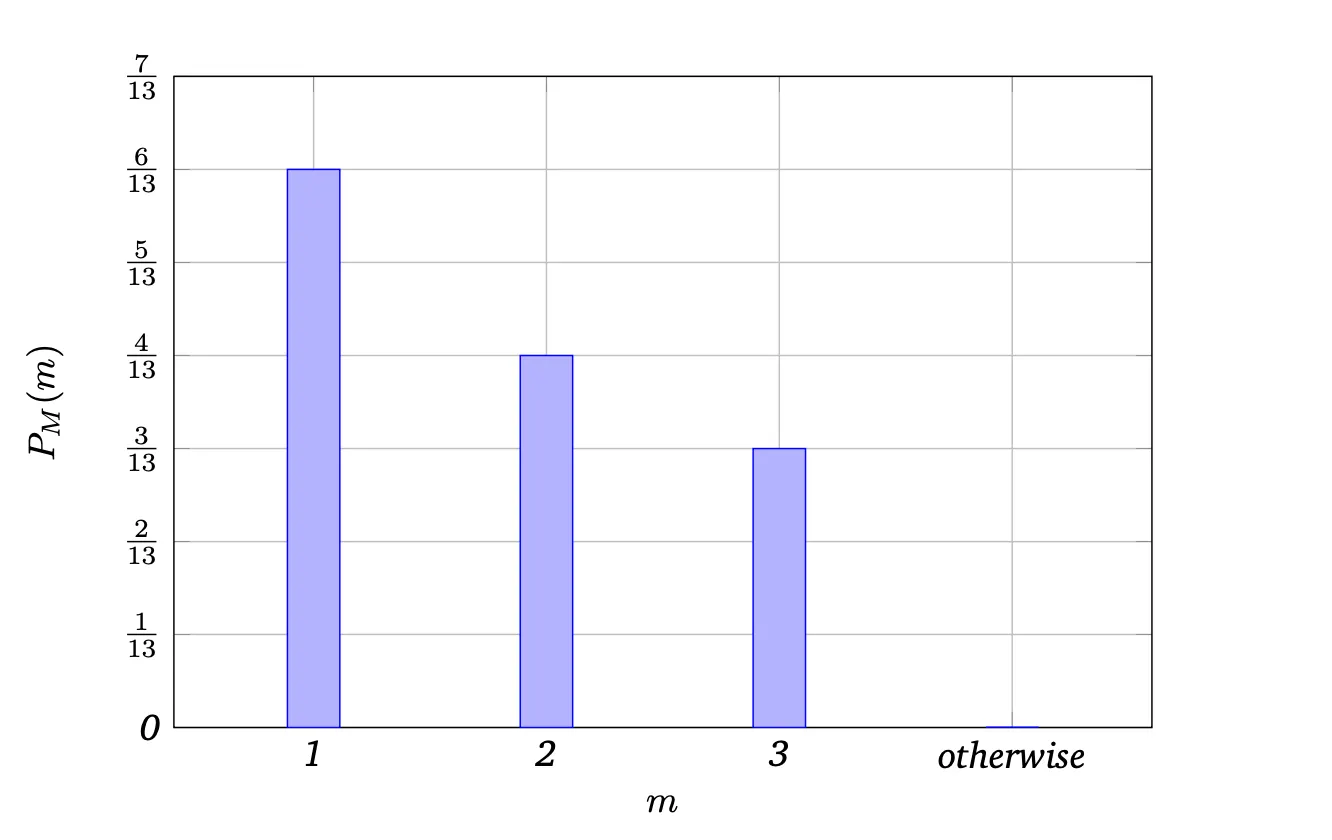

- Example 0.3. The random variable M has PMF given by

- Find:

- The value of the constant $d$.

- $P [M = 1]$.

- $P [M \geq 2]$.

- $P [M > 2]$.

- Solution

- \[\begin{gather} \sum_{m=1}^{3} P_M(m) = 1 \implies \left( \frac{2d - 1}{1 + 1} + \frac{2d - 1}{2 + 1} + \frac{2d - 1}{3 + 1} = 1 \right) \cdot 12 \\ 12d - 6 + 8d - 4 + 6d - 3 = 12 \\ 26d - 13 = 12 \\ (26d = 25) \cdot \frac{1}{26} \\ \boxed{d = \frac{25}{26}} \end{gather}\]

- $\ P[M = 1] = \frac{2 \cdot \frac{25}{26} - 1}{1 + 1} = \frac{\frac{25}{13} - 1}{2} = \frac{\frac{25 - 13}{13}}{2} = \frac{\frac{12}{13}}{2} = \boxed{\frac{6}{13}}$

- $\ P[M \geq 2] = P[M = 2] + P[M = 3] = \frac{2 \cdot \frac{25}{26} - 1}{2 + 1} + \frac{2 \cdot \frac{25}{26} - 1}{3 + 1} = \frac{\frac{12}{13}}{3} + \frac{\frac{12}{13}}{4} = \frac{4}{13} + \frac{3}{13} = \boxed{\frac{7}{13}}$

- $\ P[M > 2] = P[M = 3] = \boxed{\frac{3}{13}}$

Families of Discrete Random Variables

Bernoulli Discrete Random Variables

- Definition 0.2 (Bernoulli (p) Random Variable). X is a Bernoulli ($p$) random variable if the PMF of X has the form

where the parameter $p$ is in the range $0 < p < 1.$

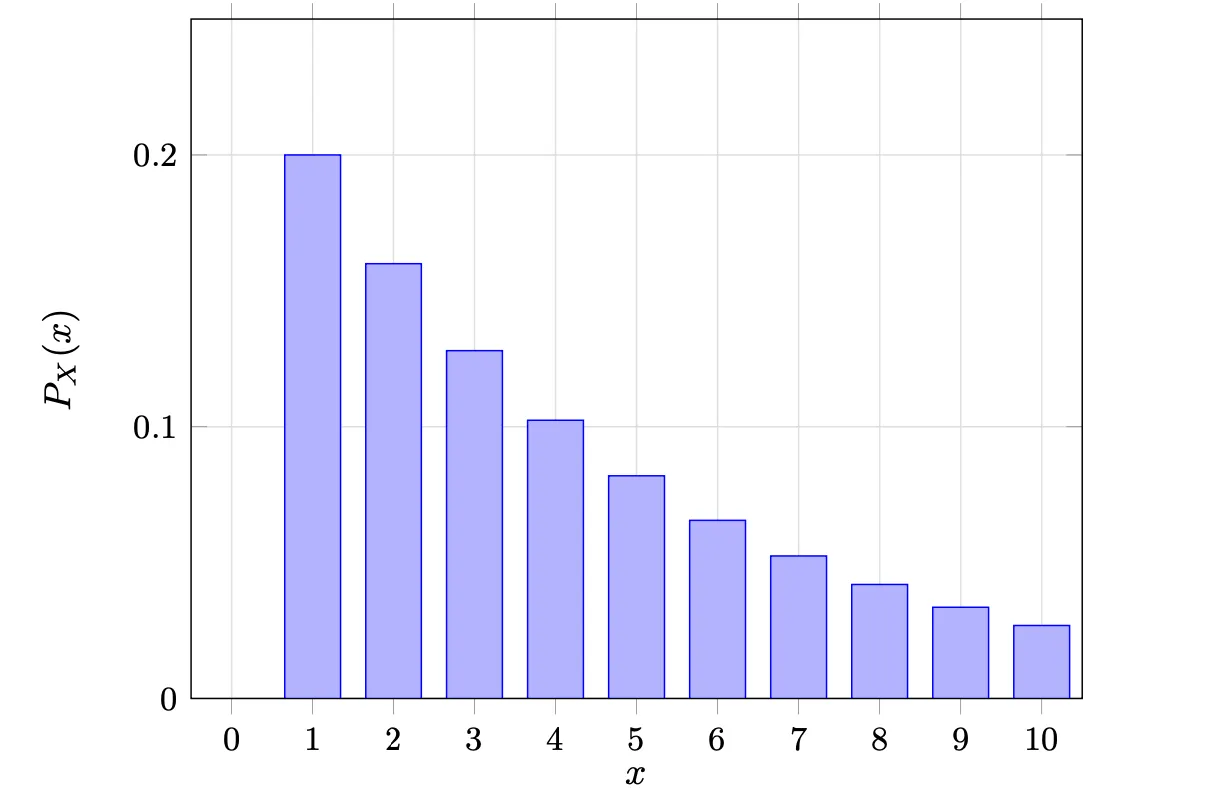

Geometric Discrete Random Variables “How many trials until the first success?”

- Definition 0.4 (Geometric (p) Random Variable). A random variable $X$ is a geometric ($p$) random variable with parameter $p$ if the PMF of $X$ has the following form:

where the parameter $p$ is in the range $0 < p < 1$.

- Example 0.5. Suppose you keep flipping a coin until you get heads. The probability of getting heads on any given flip is $p = 0.2$. Let $X$ represent the number of flips needed to get the first head. What is the probability mass function (PMF) of $X$?

- Solution:

- Graph

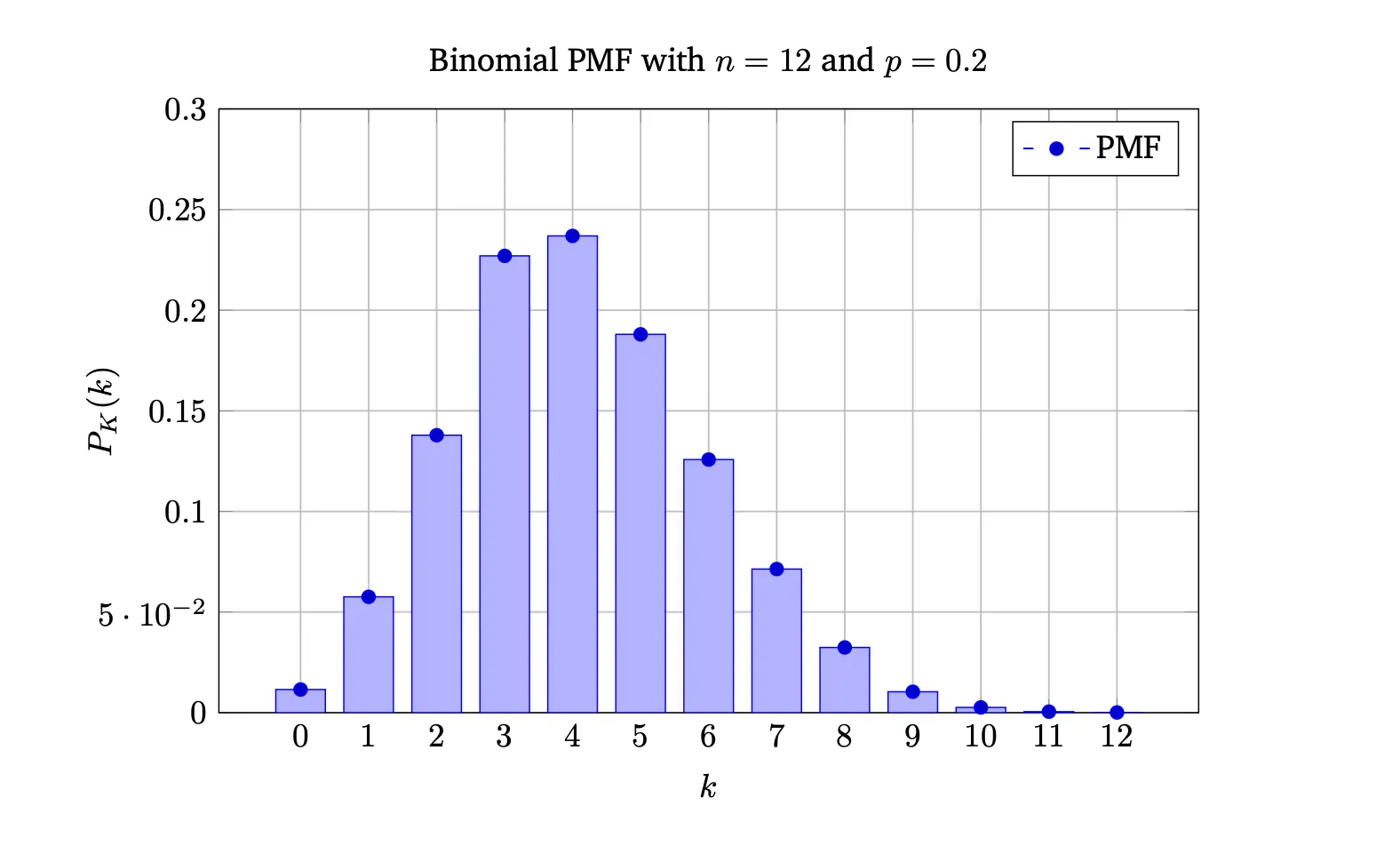

Binomial Discrete Random Variable “How many success in n trials?”

- Definition 0.6 (n choose k). For an integer $n \geq 0,$ we define:

- Definition 0.7 (Binomial (n, p) Random Variable). Let X be a binomial (n, p) random variable. The probability mass function (PMF) of X is given by:

where $0 < p < 1$ and $n$ is a positive integer ($n \geq 1$).

- Example 0.9. Suppose you flip a coin 12 times. The probability of getting heads on any given flip is p = 0.2. Let X represent the number of heads obtained in these 12 flips. What is the probability mass function (PMF) of X?

- Solution:

- Graph:

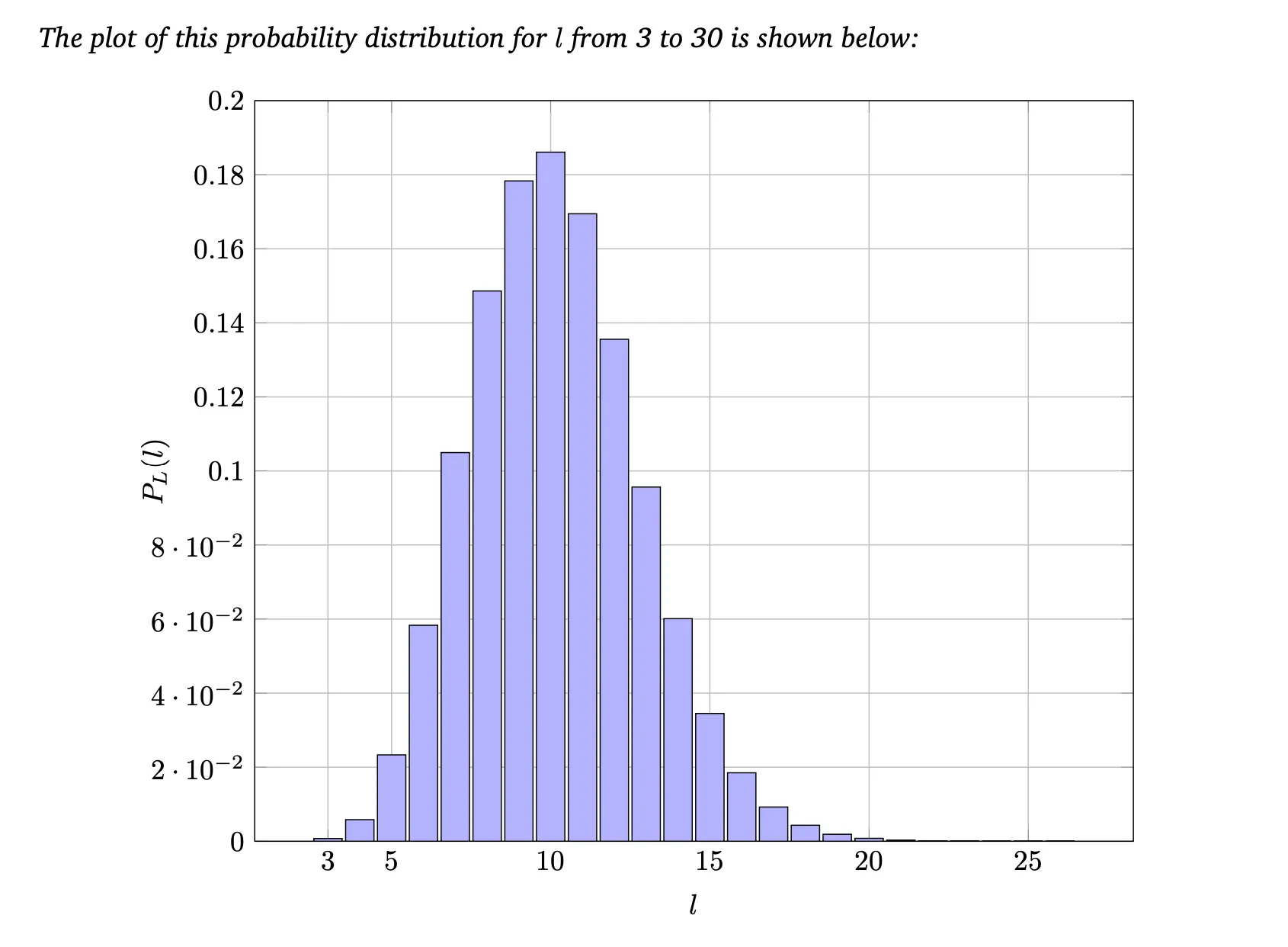

Pascal Discrete Random Variable “How many trials until the r-th success?”

- Definition 0.11 (Pascal (k, p) Random Variable). X is a Pascal (k, p) random variable if the PMF of X has the form:

where $0 < p < 1$ and k is an integer such that $k \geq 1$.

- Example 0.12. Assume the probability of a failed test is 0.1, and we are seeking to find three defective devices. The random variable L represents the number of tests necessary to find three defective devices. The PMF is:

- Solution:

- Graph:

Poisson Random Variable “How many events happen in this time?”

- Definition 0.16 (Poisson ($\alpha$) Random Variable). A random variable X is a Poisson ($\alpha$) random variable if the PMF of X has the form:

where the parameter $\alpha$ is a positive real number ($\alpha > 0$).

\[\begin{aligned} \lambda &\to \text{Average rate per second} \\ T &\to \text{time in seconds} \\ &\implies \alpha = \lambda T \end{aligned}\]- Example 0.17. The number of phone calls received at a call center in any time interval follows a Poisson distribution. A particular center receives on average ε = 3 calls per minute. Find the probability that there are no calls in a 0.5-minute interval. Also, find the probability that there are no more than four calls in a 2-minute interval.

- Solution:

\[\begin{gathered} \text{Probability of no more than 4 calls in a 2-min interval:} \\ \\ \alpha = \lambda T = 3 \cdot 2 = 6 \\ \\ P_J(j) = \begin{cases} \dfrac{6^j e^{-6}}{j!} & \text{for } j = 0, 1, 2, \dots, \\ 0 & \text{otherwise} \end{cases} \\ \\ P[J \leq 4] = \sum_{j=0}^{4} P_J(j) = P_J(0) + P_J(1) + P_J(2) + P_J(3) + P_J(4) \\ \\ \begin{aligned} P_J(0) &= \dfrac{6^0 e^{-6}}{0!} = e^{-6}, \\ P_J(1) &= \dfrac{6^1 e^{-6}}{1!} = 6e^{-6}, \\ P_J(2) &= \dfrac{6^2 e^{-6}}{2!} = 18e^{-6}, \\ P_J(3) &= \dfrac{6^3 e^{-6}}{3!} = 36e^{-6}, \\ P_J(4) &= \dfrac{6^4 e^{-6}}{4!} = 54e^{-6}. \end{aligned} \\ \\ P[J \leq 4] = (1 + 6 + 18 + 36 + 54)e^{-6} = 115e^{-6} \approx 0.527 \end{gathered}\]